Dr. Howard Fine. Photo credit: John Abbott.

Dr. Howard Fine. Photo credit: John Abbott.

Glioblastoma is a relatively rare but malignant, fast-growing and virtually always fatal brain tumor that has been historically difficult to model for the purpose of developing better treatments.

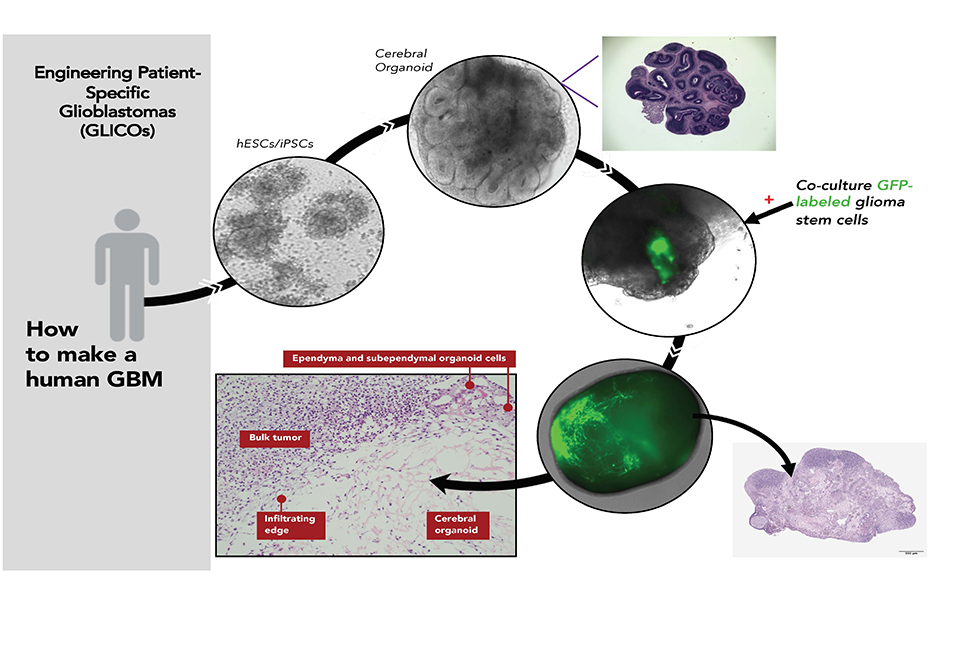

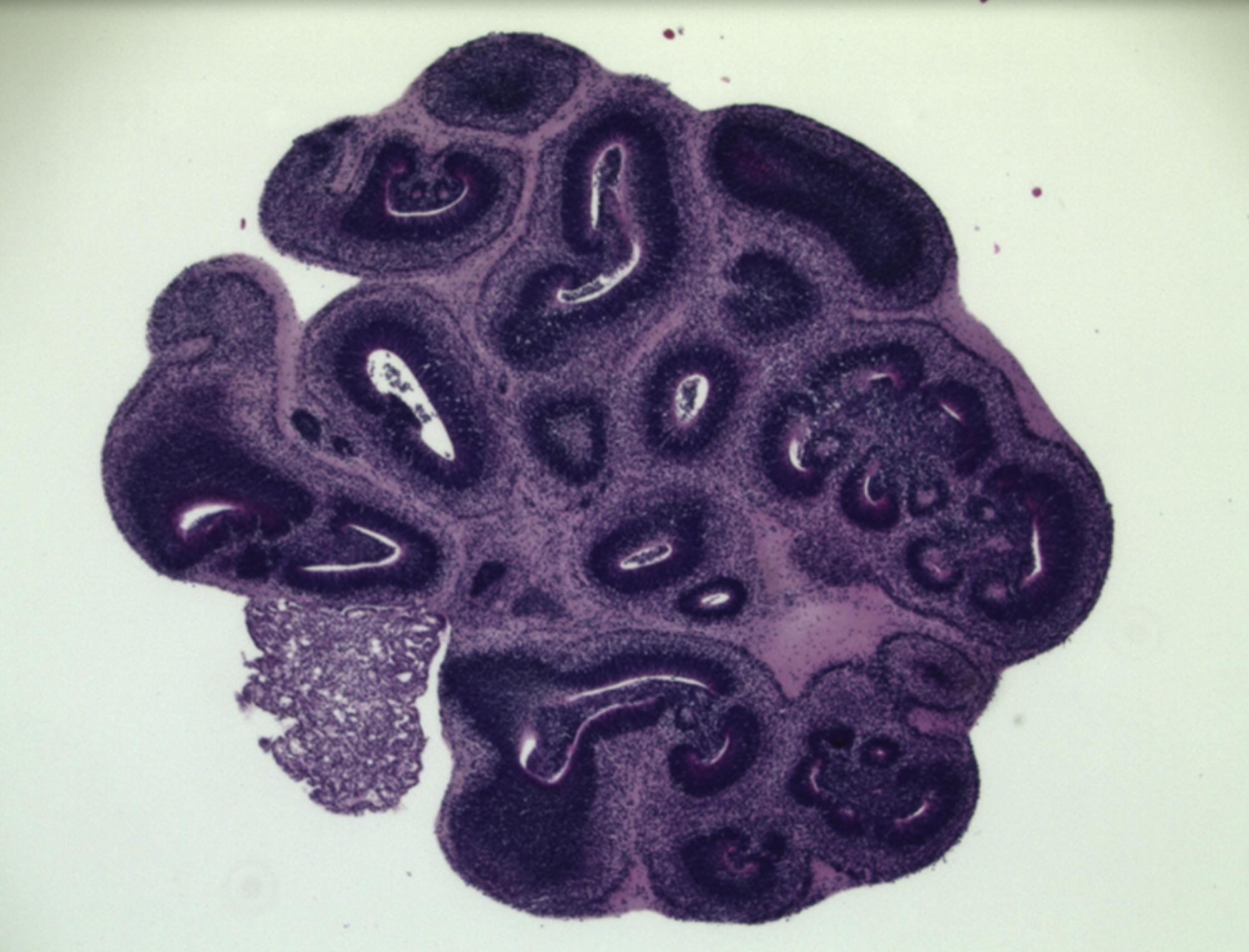

The mini brains, which are called glioblastoma cerebral organoids or GLICO, are the fruit of a more than decade-long quest by Dr. Fine. Frustrated by the lack of treatment options for his patients with glioblastoma, he set out to create a better model for studying the disease.

“The disease we were studying in the laboratory looked nothing like the disease I was seeing in the clinic,” said Dr. Fine, who is also the associate director for translational research at the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine and the founding director of the Brain Tumor Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. That has made it difficult to test drugs or to try to find the best drugs for a particular patient.

“It’s really critical to have models that capture the complexity of human tumors, so that you can use them in the laboratory to predict how well the drugs will work in the patient,” said co-senior author Dr. Olivier Elemento, director of the Caryl and Israel Englander Institute for Precision Medicine, associate director of the HRH Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud Institute for Computational Biomedicine and a professor of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Dr. Olivier Elemento. Photo credit: Jesse Winter.

Dr. Olivier Elemento. Photo credit: Jesse Winter.

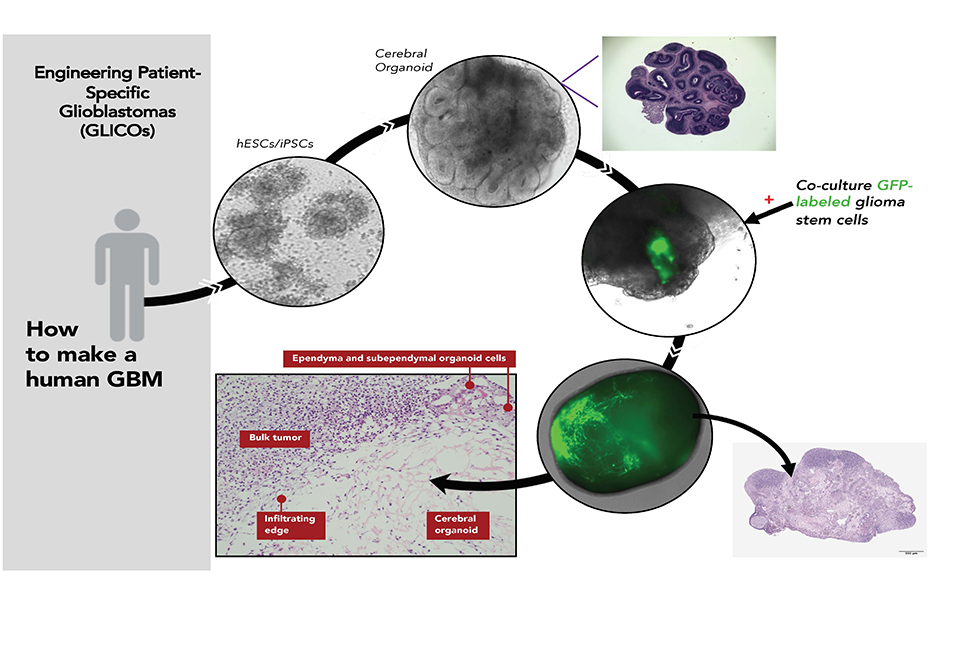

A GLICO is created by coaxing patient cells to grow into a tiny and very simple model of the brain. It is then injected with glioblastoma stem cells collected from the patient’s tumor.

The new study was designed to test how the GLICO model stacks up to three other models that grow patient tumor cells: in mice, in two-dimensional colonies in a petri dish, or into tiny three-dimensional stand-alone tumors. In the experiments, the team used single-cell RNA-sequencing to determine how well each of the models recreated the gene expression patterns seen in five patients’ tumors. Dr. Fine had set out with the hope the GLICO model would do as well as the gold-standard—the mouse model.

“We were surprised and thrilled when the results showed the GLICO models actually looked more like the patients’ tumors than tumors grown in mice,” he said. “The human brain cells are better at recreating what’s happening in the patient’s tumors.”

The results of the study likely have implications for more than just brain cancer. Dr. Elemento, who also leads joint precision medicine efforts at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, explained that the interactions among tumor cells and between normal cells and tumor cells are likely important in many types of cancers.

“This work is inspiring us to use a similar approach for growing prostate cancer in the laboratory,” he said. “We are trying to recreate the complexity of human tumors using this method of embedding cancers cells in normal cells.”

Drs. Fine and Elemento have already built a robotic system that could use hundreds of GLICOs created from a patient’s glioblastoma tumor cells to test the effects of potentially thousands of drugs. They then plan to verify that this approach helps match the patient with the treatments that will be most effective against their cancer—what Dr. Fine calls “the next level of precision medicine.”

Dr. Olivier Elemento is co-founder and equity-holder of Volastra Therapeutics and OneThree Biotech. Both companies focus on technologies related to precision medicine.

Making a patient-specific brain tumor in a model of the patient’s brain: Patient blood cells are converted to genetic replicas of the patient’s own embryonic stem cell-like cells (iPSCs). These cells are then coaxed in the lab to build a primitive replica of the patient’s own brain (cerebral organoid). Then, glioblastoma stem cells taken from the patient’s tumor are allowed to attach onto and invade the patient’s “mini brain” forming a near replica in the lab of the patient’s tumor growing in their brain.